View PDF Version of Newsletter

April 11, 2016

Robert Bingham, CFA, President and Chief Investment Officer

John Wright, Principal, Director of Research

“If you slept through the first quarter, you’d think nothing happened, but it was a nightmare of a quarter.”

– David Lyon, JP Morgan Private Bank global investment strategist

After a frightful start to the year, security markets bounced back strongly at the end of the first quarter. The S&P 500 Index fell 11.4% from December 31st to its low on February 11th, and then rebounded by 13.8% through March 31st without including dividends. For the entire first quarter, the S&P 500 gained 1.3% when including dividends while only appreciating by 0.8% without including dividends. The Dow Jones Industrial Average increased by 2.2% in the first quarter and the NASDAQ Composite declined by 2.4% when including dividends. And the BofA Merrill Lynch Government & Corporate Bond Index gained 3.5% in the first quarter.

Obviously, the quarter’s volatility impacted various parts of the securities markets quite differently. The STOXX Europe 600 Index declined by 7% in the first quarter while Brazilian markets increased by 15.5% as measured by the IBOV Index. Futures prices for refined gasoline increased by 12.6% in the first quarter, while natural gas futures declined by 16.2%, as measured respectively by the XB1 and NG1 commodity contracts. Utility stocks did well in the first quarter, while financial and health care stocks underperformed.

January’s fear of a global recession appears to have been replaced by an expectation that global economic growth will muddle along. So although security markets remain unsettled, we’ve made progress, and we are better off than where we were at the start of the year. Importantly, job growth in the American economy has continued to grow despite weak economic growth. Growth of U.S. employees on nonfarm payrolls was 5.6% higher in the past six months than in the comparable period of November 2014 through April of 2015. In contrast, gross domestic product growth fell below 2% in 2015 from the 2.5% levels seen in 2014 and 2013.

First quarter earnings will also soon be released. While FactSet Research Systems expects weak overall first quarter earnings, we may find the results better than anticipated. Similar concerns have been overstated these last few years as S&P 500 companies have on average exceeded estimated earnings by 4% over the last four years. FactSet does, however, also expect the first quarter earnings to be weaker than they previously anticipated at the end of March. As of April 8th, FactSet expected 2016’s first quarter earnings for the S&P 500 companies to be 9.1% lower than the 2015 levels.

These results, however, could be a low point since S&P 500 composite earnings are heavily impacted by the value of the U.S. dollar. With the U.S. dollar declining in the first quarter against the Euro and many other international currencies, earnings results for those companies with substantial international sales may be better as a result. The Euro increased by 5% in the first quarter versus the U.S. dollar, so the value of an American company’s European sales may have grown by 5% in the first quarter everything else being equal.

Such trends may have been anticipated in the first quarter by emerging market securities which posted strong results. Many of these economies depend on the sale of their own natural resources into world markets, and these sale prices most often are quoted in U.S. dollars. So as the dollar declined in February and March, the economic prospects for emerging markets improved markedly. Hence, the MSCI Emerging Markets Index increased 21.9% in the first quarter off its five year low as seen on January 21st. Hopefully, that strong bounce is a harbinger of growth in other world economies as well as for the United States this year.

Clearly, risks remain. For several years, central banks around the world have been trying to fight anemic growth trends while warding off deflation. While noble in effort, these bankers have not been getting any help from their legislators and government leaders. The European Central Bank (ECB) continues to expand its bond buying program and has in fact had banks pay it interest if banks leave deposits on account at the ECB. Similarly, the Bank of Japan has expanded its bond buying program and is also paying negative rates of interest to its national banks. These negative interest rates are supposed to incite local banks to make loans with those deposits rather than keep those monies on account and in reserve.

These central bank bond-buying efforts have driven down interest rates across the world. As a result, bank profit margins have declined to levels that make some lending efforts unprofitable. So in this negative and low rate environment, credit is being extended more freely to the stronger and lower risk borrowers – governments, larger corporations, and wealthy individuals. Small savers, small businesses, and those with lower incomes are having more difficulty obtaining capital. David Malpass of Encima Global LLC estimates that “the U.S. banking system has had to devote nearly 20% of total bank assets to the Fed’s bond purchases at the expense of other lending.” (“The World’s Monetary Dead End” – WSJ 1/22/15). He also calculates that, “In the past five years, total U.S. credit grew only 20%, compared with at least a 40% increase in most previous expansions.” (“Don’t Blame the Fed’s Interest-Rate Baby Step” – WSJ 2/10/16).

Unfortunately, government policies to encourage capital spending, research and development, and other private investments have not been furthered in Europe, America, or Japan. Corporate CEOs have therefore been trying to lower expenses while expanding sales. Yet, efforts by companies to improve efficiencies and reduce operating expenses have often run into government roadblocks.

In 2010, the Dodd-Frank Act became a tool for U.S. financial regulators to oversee and control “systemically important institutions.” As a result, MetLife along with JPMorgan Chase, Wells Fargo, General Electric and others, were deemed “too-big-to-fail” by the Financial Stability Oversight Council. These companies were instructed to shrink their balance sheets, reduce their operating leverage, and raise more capital. Such steps were designed to reduce risk while also reducing growth and profit levels.

MetLife decided to sue the U.S. government for classifying it as a “systemically important institution,” and on March 30th, MetLife won its case. Yet, this victory was short lived since the U.S. Justice Department appealed the case on April 8th, and MetLife’s legal battle continues. From the get-go, we were surprised that MetLife was deemed “too-big-to-fail” since its business is not subject to the immediate withdrawals that the banking industry faces. Even former Connecticut Insurance Commissioner Tom Leonardi remarked, “All of the relevant state insurance regulators, myself included, were publically opposed to MetLife’s designation.”

General Electric decided to comply with the Financial Stability Oversight Council’s ruling and shrank its balance sheet and redirected its business accordingly. They now have filed to be removed from the “too-big-to-fail” list since they have reduced their balance sheet by more than 50% since 2012 and their use of commercial paper by 90%. We would expect the U.S. government to agree with GE’s request, but when and with what stipulations remains to be seen. Meanwhile, GE exports over “$20 billion worth of American-made goods to the world” and these sales “support our manufacturing base here at home,” (GE CEO, Jeffrey Immelt, Washington Post 4/6/16). Mr. Immelt also points out that “U.S. companies continue to wrestle with an outdated and complex tax code that puts them at a distinct competitive disadvantage. The U.S. tax system has not been updated in 30 years and isn’t designed for today’s economy.”

Since tax reform changes have been long delayed, Pfizer chose to merge with Allergan PLC of Ireland. This merger was classified as an inversion since Pfizer would move its legal headquarters to Ireland. Pfizer would then be able to rebalance its earnings worldwide and lower expenses with lower international tax rates.

Understandably upset by this strategy, the U.S. Treasury imposed rules specific to Pfizer and Allergan that forced the two companies to end their merger. While it is easy to lambast an inversion’s tax avoidance strategy, our country should really be trying to get foreign companies to relocate to America instead, rather than simply applying one set of rules to one company and different rules to another. As Pfizer CEO Ian Read asked, “If the rules can be changed arbitrarily and applied retroactively, how can any U.S. company engage in the long-term investment planning necessary to compete?” (Treasury Is Wrong About Our Merger And Growth – WSJ 4/7/16).

Markets want answers to such questions. What strategies are companies pursuing, what earnings prospects should be expected, and what surprises should be anticipated? Without understandable answers, markets will hesitate, change directions, and react with a vengeance. On April 5th, after Pfizer and Allergan ended their merger negotiations, Allergan’s stock fell on the opening by 17%. Pfizer’s stock traded higher by 2.1% that day.

Markets will be penalizing and volatile if corporate strategies appear flawed. In response, managements have increasingly avoided risk, reduced their level of capital spending, collected cash, and bought back stock. Bloomberg’s Lu Wang calculates that the S&P 500 companies have spent more than $2 trillion on stock repurchases since 2009. And in the first quarter, she estimates that $165 billion may have been spent – a record level last seen in 2007. Recent economic growth may have been that much stronger if investment spending had been more widely encouraged instead.

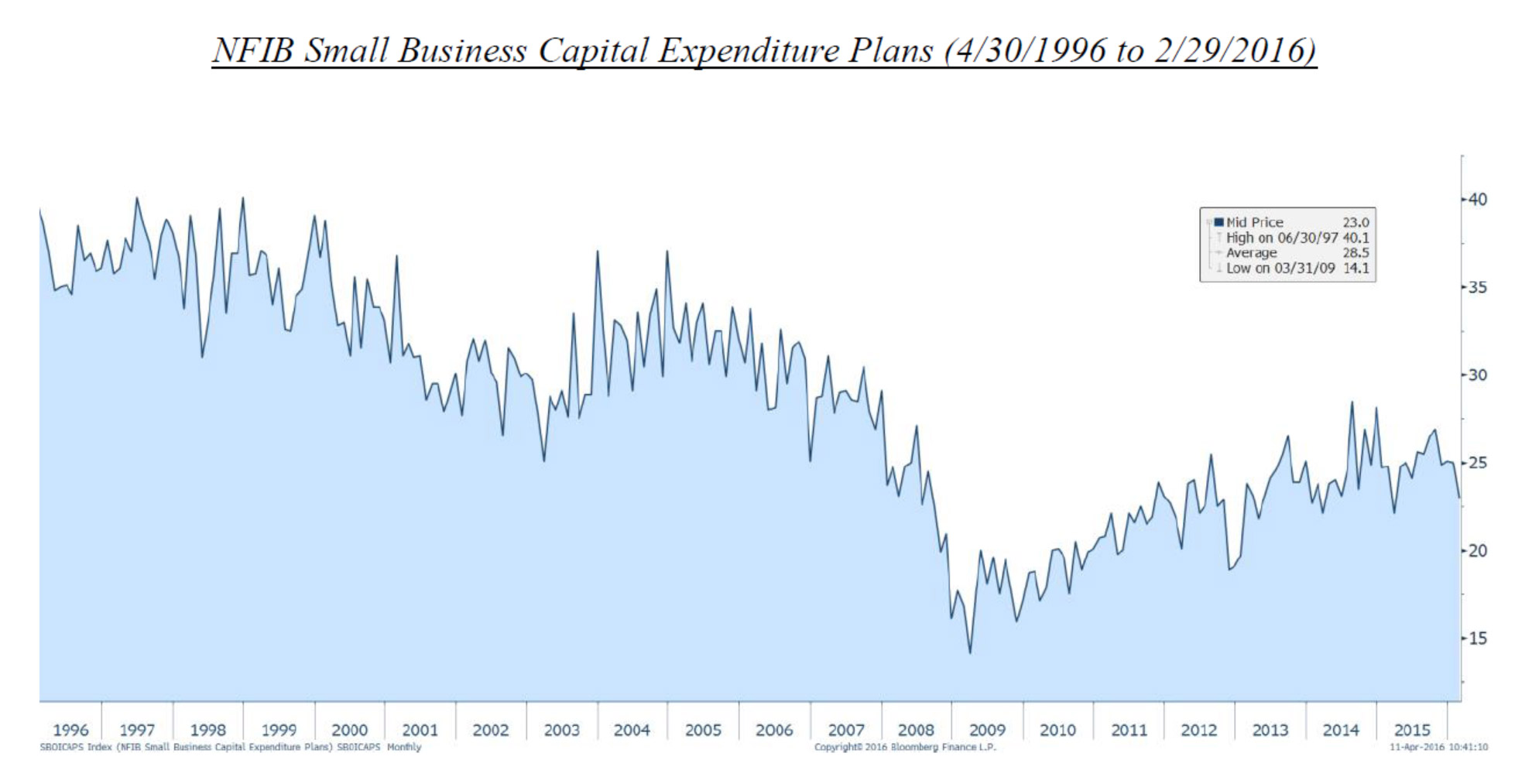

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York surveys U.S. business leaders on a monthly basis to track business sentiment for various sectors of the economy. Other Federal Reserve Banks also collect capital spending data. And the National Federation of Small Business also tracks capital expenditure plans on both an actual and intended basis. In almost every study, the numbers are weaker today than they were in 2011 and 2012. While the numbers are better than those of 2008 and 2009, they often remain lower than the levels from the 1995 to 2005 time period. The graph below from the National Federation of Independent Business depicts this trend.

Hence, we look at various issues and factors when we build portfolios for our clients. And while current markets remain uncertain, that is most often always the case. We still believe the U.S. economy will continue to grow and that investors should still be concerned about inflation risks. Food and labor costs appear to be rising, and as Allen Sinai, Decision Economics CEO, states, “We are at an inflection point on inflation. The risks are shifting from downside surprises on inflation to watching out for the upside surprises.” Thankfully, the Federal Reserve’s bond buying program has been reduced, and thankfully also, our Federal Reserve is not likely to adopt a negative interest rate policy anytime soon.

So we still expect the markets to trend higher, and perhaps the markets may even surprise us on the upside. But either way, we still advocate a balanced portfolio with an emphasis on capturing yield. Through market ups and downs, a portfolio’s yield and the resulting cash flow generate returns while also allowing all of us to pay some expenses.

Do let us know if you have any questions or would like to visit.

Securities noted above valued as of the market close on April 8, 2016:

Allergan PLC (AGN $236.00)

General Electric Company (GE $30.79)

JPMorgan Chase & Co. (JPM $57.74)

MetLife, Inc. (MET $41.89)

Pfizer Inc. (PFE $32.50)

Wells Fargo & Company (WFC $47.07)

The above summary/prices/quotes/statistics contained herein have been obtained from sources believed to be reliable but are not necessarily complete and cannot be guaranteed. Errors and omissions excepted.